Items

-

PersonSadlier, Anna Theresa (1854 – 1932)Anna Teresa (sometimes "Theresa") Sadlier was born in Montreal, Canada, 1854. Her father was James Sadlier and her mother was Mary Anne Sadlier. Her education was received at various schools in that city, and completed at the Villa Maria, the principal Convent of the Congregation of Notre Dame of Montreal. Like her mother, she spent about equal portions of her life in New York City and Montreal. She was a frequent contributor in prose and verse to most of the U.S. Catholic periodicals as well as to some English and Canadian ones. She wrote a great many short stories. One of her earliest literary ventures was Seven Years and Mair, a novelette published by the Harpers in their "Half Hour Series". Her principal original published works were “Names that Live” and “Women of Catholicity”, two volumes of biography. Sadlier spent a lot of time on these and they possessed a historical point of view. In two of the sketches which were distinctively American, she drew largely from “The Jesuit Relations” and the “Memoirs of Père Olier”, and she had the advantage of access to the annals of the Ursulines of Quebec and of the Congregation of Notre Dame of Montreal. Among her other original works are two stirring historical romances, “The Red Inn of St. Lyphar”, which finds its plot and its adventures in the days of the French Revolution and the Rising of La Vendee; and “The True Story of Master Gerard”, in which the background is provided by Colonial New York and the Leisler conspiracy. Perhaps Sadlier's best work was accomplished in juvenile fiction. In “The Mysterious Doorway” and “The mystery of Hornby Hall”, she provided, as the titles imply, a mystery, while the children in “The Talisman and A Summer at Woodville” are lifelike, interesting, lovable youngsters, and the heroine of ”Pauline Archer” is a Catholic cousin of “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm”. Sadlier's translations from the French and Italian include: “Ubaldo and Irene”, “Mathilda of Canossa”, “Idols”, “Monk's Pardon”, “The Outlaw of Camargue”, “The Wonders of Lourdes”, “The Old Chest”, “Consolations for the Afflicted”, etc. Sadlier was the founder of the Ottawa Tabernacle Society. She resided in Ottawa, Ontario for 29 years, before dying there at her home, April 16, 1932. The interment was at Ottawa's Notre Dame cemetery.

-

PersonDe la Ramée, Marie Louise (1839 - 1908)Maria Louise Ramé was born at Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England. Her mother, Susan Sutton, was a wine merchant's daughter; her father was from France. She derived her pen name from her own childish pronunciation of her given name "Louise". For many years Ouida lived in London, but in about 1871 she moved to Italy. In 1874, she settled permanently with her mother in Florence, and there long pursued her work as a novelist. At first, she rented an apartment at the Palazzo Vagnonville. Later she removed to the Villa Farinola at Scandicci, south of Bellosguardo, three miles from Florence. She lived in Bagni di Lucca for a period, where there is a commemorative plaque on an outside wall. She declared that she never received from her publishers more than £1600 for any one novel, but that she found America "a mine of wealth". In “The Massarenes” (1897) she gave a lurid picture of the parvenu millionaire in smart London society. This book was greatly prized by Ouida, and was very successful in terms of sales. Thenceforth she chiefly wrote for the leading magazines essays on social questions or literary criticisms, which were not remunerative. As before, she used her locations as inspiration for the setting and characters in her novels. The British and American colony in Florence was satirized in her novel, “Friendship” (1878). She continued to live in Italy until her death on 25 January 1908, at 70 Via Zanardelli, Viareggio, of pneumonia. She is buried in the English Cemetery in Bagni di Lucca, Italy. During her career, Ouida wrote more than forty novels, children's books, and collections of short stories and essays. Her work had several phases. In 1863, when she was 24, she published her first novel, "Held in Bondage". In her early period, her novels were considered "racy" and "swashbuckling", a contrast to "the moralistic prose of early Victorian literature" (Tom Steele), and a hybrid of the sensationalism of the 1860s and the proto-adventure novels being published as part of the romanticisation of imperial expansion. Later her work was more typical of historical romance, though she never stopped commenting on contemporary society. She also wrote several stories for children. The British composer Frederic Hymen Cowen and his librettists Gilbert Arthur à Beckett, H. A. Rudall, and Frederic Edward Weatherly acquired the rights to Ouida's 1875 novel “Signa” to create an opera for Richard D'Oyly Carte's Royal English Opera House to succeed Arthur Sullivan's Ivanhoe in 1891. Between Cowen not being ready with his work and the collapse of Carte's venture, Cowen eventually took his finished opera “Signa” to Italy with an Italian translation of the original English text by G.A. Mazzucato. After many delays and production troubles, Cowen's “Signa” was first performed in a reduced three-act version at the Teatro Dal Verme, Milan on 12 November 1893. After further revision and much cutting, it was later given in a two-act version at Covent Garden, London on 30 June 1894, at which point Cowen wondered if there was any sense left in the opera at all. Ouida's impression of the work is unknown. Later, Pietro Mascagni bought the rights for her story "Two Little Wooden Shoes", intending to adapt it for an opera. His friend Giacomo Puccini became interested in the story and began a court action, claiming that because Ouida was in debt, the rights to her works should be put up for public auction to raise funds for creditors. He won the court challenge and persuaded his publisher Ricordi to bid for the story. After Ricordi won, Puccini lost interest and never composed the opera. Mascagni later composed one based on the story, under the title “Lodoletta”.

-

PersonTrask, Katrina (1853 – 1922)In 1878 she wrote Colorado Leaves, and in 1888 the Chronicles of Yaddo. Her first book, "Under King Constantine", was published anonymously in 1892. The book contains three long love poems and was written in three days under intense mental strain. She hid the poems away for years until finally persuaded by her husband to have them published. It went through five editions and beginning with the second edition she started identifying herself as Katrina Trask. She published "Free Not Bound" (1903), a novel, and "Night & Morning" (1907), a narrative in blank verse; both were about love and marriage. In 1908 she wrote "King Alfred’s Jewel", a historical drama also in blank verse. As an avid pacifist, she wrote an antiwar play, "In the Vanguard" which appeared a year before World War I and went through eight editions and was performed by women clubs and church groups.

-

PersonMitchell, Ellen M. (1838 –1920)Ellen M. Smith was born in the Village of Geddes, New York to Harriet H. Rowland and Edwin R. Smith, the eldest of their four children. She graduated from the Cortland Academy, Homer, N.Y. in 1860, with a major in classics. During the Civil War her brother, Edwin R. Smith, Jr., served in New York's 149th Regiment. Edwin was killed in the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 3, 1863. Ellen adopted the pen name "Ella Ellwood" in identification with Edwin, writing with the name Ellwood during the war. Following Edwin's death, Ellen resigned her teaching position in Syracuse and moved to Cairo, Illinois, where she lived with her uncle, Ward L. Smith and his wife, Anna. During the war, Ellen moved to St. Louis, Missouri. She wrote for the Missouri Republican newspaper of St. Louis, continuing to use the pen name Ella Ellwood until the war's end. She married St. Louis attorney and Union civil war veteran Joseph W. Mitchell in the Presbyterian Church of Alton, Illinois in September, 1867. While in St. Louis, she attended the Hegelian philosophy lectures which had been organized there by William T. Harris. She and Joseph also contributed to a literary and philosophical discussion group called "The Pen & Pencil Club," often hosting the meetings in their home. Ellen and Joseph moved to Denver, Colorado in 1878, seeking effective treatment for Joseph's illness (possibly tuberculosis). However, Joseph died in February, 1879. Ellen remained in Denver, where she taught school and, then, lectured on philosophy and literature in the University of Denver. Also, she actively contributed to the Kant Club, and to the Fortnightly Club, of Denver. Mitchell attended the first session, in July 1879, of the Concord Summer School of Philosophy, which was hosted in Concord, Massachusetts, by Bronson Alcott on his property. William T. Harris organized the school and its programs after leaving St. Louis, with the intention of unifying the Hegelian Idealism of the St. Louis Philosophical Society with the Transcendentalism of Concord. At that first 1879 session, Ellen became acquainted with many women from across the country who were leading the struggle for women's suffrage, as well as the efforts to improve educational and social policy standards. Among those she met while attending the 1879 Concord session was Julia Ward Howe who, later, became the president of the Association for the Advancement of Women. The Concord School played an important role in helping to build networks of policy reformers; more than one half of those who attended were women. Mrs. Mitchell participated in the annual Concord School of Philosophy every year, until its final session in 1888. She wrote, in 1880, a description of the lectures during the previous session, and she delivered a paper titled "Friendship in Aristotle's Ethics" during the Concord session of July, 1887. Mitchell actively contributed to the Association for the Advancement of Women, regularly attending the annual congresses. At the 12th Woman's Congress in 1884, held at Baltimore, she delivered a paper titled "A Study of Hegel." Throughout her career, Mitchell advocated, and endeavored to realize, the noble aspiration for American philosophy which was advocated by Walt Whitman in his great poetic essay manifesto of 1871, "Democratic Vistas". In Syracuse, she organized and led the Round Table of Syracuse, a literary and philosophical community adult seminar group. The Round Table began in 1894 and continued for more than 20 years. To assist the participants in their studies and discussions, Mitchell wrote and privately published a series of essays on Dante, Tennyson, and Goethe. The title for one of the essays, "The Way of the Soul" is adapted from Hegel's introduction to his Phenomenology of Spirit. Mitchell died in Syracuse, N.Y. May 14, 1920 at the age of 81. She is interred beside her parents in the Myrtle Hill Cemetery of the Village of Geddes. In her obituary, May 16, 1920, the Syracuse Herald newspaper commented: "The Herald records with sincere regret the death of Mrs. Ellen M. Mitchell, for many years the gentle preceptor and oracle of the Syracuse Round Table. The value of her services to the literary life of the city cannot easily be overestimated....Mrs. Mitchell's personality was singularly lovable, and it imparted a magnetic charm to her discourse and her teaching. On its intellectual side the City of Syracuse is much the poorer by her death”.

-

PersonHarrison, Elizabeth (1849 - 1927)Elizabeth Harrison was born in Athens, Kentucky, the fourth child of Elizabeth Thompson Bullock and Isaac Webb Harrison. According to the 1850 census, Isaac Harrison was a merchant there. The family moved to Midway, Kentucky, then to Davenport, Iowa, where by 1870 he was described in the census as a land agent. Elizabeth Harrison was invited to Chicago in 1879 by her friend Mrs. W.O. Richardson to pursue a career in education. After encountering the early kindergarten movement in Chicago and studying with early kindergarten educator Alice Putnam, Harrison sought further training in St. Louis and New York. She then taught kindergarten in Iowa and Chicago. Involving mothers in education, Harrison and Putnam founded the Chicago Kindergarten Club in 1883, influenced by the book Mothers at Play by Friedrich Fröbel. In 1886, Harrison founded a training school for kindergarten teachers in Chicago. Intrigued by the ideas used by a German woman working at her school, Harrison decided to find out more. She tracked these ideas back to the Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus in Berlin and in 1889 she traveled there to study. On her return she renamed her institution the Chicago Kindergarten Training College. Harrison's school became an innovative college of education. She was president of the college, expanded to the National Kindergarten and Elementary College, until her retirement in 1920. It is now part of National Louis University. In 1903 Harrison co-wrote “The Kindergarten Building Gifts” with Belle Woodson, Instructor in Gifts and Occupations of the Chicago Kindergarten College. During her career, Harrison wrote a number of books, including: “A Study of Child Nature” (1890 – which saw 50 editions published in the following years), “In Storyland“(1895), “Some Silent Teachers” (1903), “Misunderstood Children” (1908), “Montessori and the Kindergarten” (1913) and “The Unseen Side of Child Life” (1922). In 1893, the college published Harrison's book, “The Kindergarten as an Influence in Modern Civilization”, in which she explained, "how to teach the child from the beginning of his existence that all things are connected [and] how to lead him to this vital truth from his own observation”. Harrison's autobiography, “Sketches Along Life's Road”, was edited and published in Boston in 1930, after her death.

-

PersonAldrich, Anne Reeve (1866 - 1892)Aldrich was born in New York City on April 25, 1866. Her father died when she was eight; her mother moved to the country, where she educated Aldrich. By the time she was a teenager, Aldrich was proficient in composition and rhetoric, and was able to translate French and Latin literature into English. Aldrich wrote poetry often from a young age. At age 17, she was published in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine. Poems in other periodicals followed and eventually led to published collections of poems. Her first volume of poetry, The Rose of Flame, was published in 1889. A second volume, Songs About Love, Life, and Death, was published posthumously. Aldrich died at the age of 26 in New York on June 28, 1892.

-

PersonWall, Annie Russell (1835 - 1920)Annie Russell Wall was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, July 18n 1835. Her parents were William A. Wall, a New Bedford artist of note, and Rhobe T. (Russell) Wall, descended from John Russell who settled in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, in the 17th century. After passing her early life in New Bedord, Wall went to Cambridge, Massachusetts to teach and later to Washington University in St. Louis , Missouri. She was associated with John Fiske. After her return to New Bedford, circa 1900, Wall became corresponding secretary of The Alliance of the First Congregational Society, an office which she filled until her death. She was a Life Member of the Alliance of Unitarian and Other Liberal Christian Women. A lifelong student of history, general and ecclesiastical, Wall gave each year in the Unitarian Chapel in New Bedford courses of Bible lectures. Annie Russell Wall died in New Bedford, May 8, 1920.

-

PersonThomas, Edith Matilda (1854 - 1925)Born in Chatham Center, Ohio, Edith Thomas was educated at the normal school of Geneva, Ohio, and attended Oberlin College (though she had to drop out). She taught school for two years, and then became a typesetter. She began writing early for the local newspapers, then was encouraged by author Helen Hunt Jackson to send verse to more important periodicals. She "gained national attention with her poetry.... Scribner's, The Atlantic Monthly, The Century and other prominent magazines published her poems." Jackson's "enthusiasitic endorsement produced almost immediate literary celebrity." In 1884, Canadian poet Charles G.D. Roberts wrote of her that "as far as I am aware her poems are not yet gathered in book form, and are therefore only to be obtained, few in number, by gleaning from the magazines and periodicals. Yet so red-blooded are these verses, of thought and of imagination all compact, so richly individual and so liberal in promise, that the name of their author is already become conspicuous.... We are justified in expecting much from her genius." Her first volume appeared in 1885 entitled A New Year's Masque and Other Poems. In 1887 she moved to New York City, where she worked for Harper's and Century Dictionary. She lived in New York for the rest of her life. She published over 300 poems between 1890 and 1909, although "the demands of the leading literary magazines constantly exceeded her supply." On her death she was called "one of the most distinguished American poets” by The New York Times. Her Selected Poems came out in 1926, a year after her death.

-

Agent

-

Location

-

PersonThaxter, Celia (1835 - 1894)Celia Laighton was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, June 29, 1835, but the family moved soon after to the Isles of Shoals, first on White Island, where her father, Thomas Laighton, was a lighthouse keeper of the Isles of Shoals Light, and then on Smuttynose and Appledore Islands. The gradual addition of summer visitors to the fishing population came slowly, Thaxter's father being the first to establish anything like a modern hotel. The means of education were comparatively remote, and the permanent society of the islands for the greater part of the year offered very limited resources for a bright child. During the period of 1849–1850, she attended Mount Washington Female Seminary in South Boston. On September 13, 1851, at the age of 16, she married Levi Thaxter and moved to the mainland, residing first in Watertown, Massachusetts, at a property his father owned. Her first published poem was written during this time on the mainland. That poem, "Land-Locked", was first published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1861 and earned her US$10. In 1879, Thaxter suddenly became known upon the literary horizon with a collection of poems entitled “Driftwood”, and considering that they came from a group of islands, away from the mainland far enough to prevent frequent communication, the debuting work was received with almost as much surprise as pleasure. Her poetry appeared in the Atlantic, Century, Harper's, Independent, New England Magazine, and Scribner's, while her writing for juvenile audiences appeared in Our Young Folks and St. Nicholas. Thaxter died suddenly while on Appledore Island in 1894.

-

PersonColquhoun Walford, Lucy Bethia (1845 - 1915)Walford was born Lucy Bethia Colquhoun on 17 April 1845 at Portobello, a seaside resort then outside Edinburgh, the seventh child of Frances Sarah Fuller Maitland (1813–1877), a poet and hymn writer and John Colquhoun (1805–1885) of Luss, Dunbartonshire, author of The Moor and the Loch. Her paternal grandmother, Janet Colquhoun (1781–1846), was a religious writer, and her aunt, Catherine Sinclair (1800–1864) was a prolific novelist and children's writer. Walford was educated privately by German governesses. Her reading included works by Charlotte Mary Yonge and Susan Ferrier, and in later years Jane Austen. The family moved to Edinburgh in 1855, where guests included the artist Noël Paton, who encouraged her to take up painting. In 1868 and several succeeding years she exhibited at the annual exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy. Her first short piece of writing appeared in the Sunday Magazine in May 1869. On 23 June 1869 she married Alfred Saunders Walford (died 1907), a magistrate of Ilford, Essex, and they moved to London. She died on 11 May 1915 at her home in Pimlico, London.

-

PersonAlden Ward, May (1853 - 1918)May Alden was born in Mechanicsburg, Ohio, one of three children of Prince William Alden (a merchant and banker) and Rebecca (Neal) Alden. She was a descendant of Captain John Alden, who came to America on the Mayflower. She early developed an interest in literature and languages and by the age of 16 was contributing articles to a Cincinnati periodical. She graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1872 at the age of 19 and a year later married William G. Ward, who held various academic positions over his career including history professor at Baldwin University and later English literature professor at Syracuse University in New York and at Emerson College in Boston. May Alden Ward traveled for two years in Europe to continue her study of Italian, French, and German literature. In 1887, she published a life of Dante, followed four years later by a life of Petrarch. Reviewers praised these books for their skillful synthesis of the existing scholarship, and the New York Times singled out Ward's lively, clear prose style and historian's instinct. Author William Dean Howells commented that her work removed "the stain and whitewash of centuries" to reveal the underlying historical truth. Her subsequent book on John Ruskin, Leo Tolstoy, and Thomas Carlyle, Prophets of the Nineteenth Century, was hailed as masterly. Ward also lectured on French and German literature and became a popular speaker on the women's club circuit. In the late 1890s, Ward and her family moved to Massachusetts, where she served as president of various organizations including the New England Women's Club (succeeding the poet Julia Ward Howe in that role), the New England Woman's Press Association, and the Cantabrigia women's club. She was also a charter member of the Authors' Club of Boston and one of the Massachusetts state commissioners for the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904. She was killed in an accident when the car she was riding in on her way home from an evening lecture collided with an electric streetcar in Boston.

-

PersonRobinson Shattuck, Harriette Lucy (1850 - 1937)Harriette Lucy Robinson was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, December 4, 1850. She was the oldest of four children of William Stevens Robinson and Harriet Jane Hanson Robinson. Her siblings were: Elizabeth Osborne (b. 1852), William Elbridge (1854-1859), and Edward Warrington (b. 1859). Shattuck was educated in the Malden, Massachusetts public schools. In addition to studying law, she had the advantage of several years of literary training under the supervision of Theodore D. Weld, of Boston. As an adult, she continued to be a student in various subjects, philosophy and politics being the chief ones of her late years. Soon after leaving school, she began to write stories for children and articles for the newspapers on different subjects, mainly relating to women. When her father was clerk of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, she served as assistant clerk, being the first woman to hold such a position in that State (1871–72). Shattuck served as a clerk in the office of the American Social Science Association in Boston. During the five or six years of the Concord Summer School of Philosophy, she wrote letters for the Boston Evening Transcript, in which the philosophy of the various great teachers, such as Plato, Hegel, Dante and Goethe, was carefully elucidated and made available to the general public. “The Story of Dante's Divine Comedy” (New York, 1887) was the outcome of those letters from the Concord school. Her other books, are Our Mutual Friend (Boston, 1880), a dramatization of Dickens, and Little Folks East and West (Boston, 1891), a book of children's tales. She was interested in all movements for the advancement of women, especially in the cause of women's political enfranchisement. She made her first speech for suffrage in Rochester, New York, in 1878. Thereafter, she spoke before committees of Congress and of the Massachusetts legislature, and in many conventions in Washington, D.C. and elsewhere. She was the presiding officer over one of the sessions of the first International Council of Women, held in Washington, D.C., in 1888. She was a quiet speaker and made no attempts at oratory. Her best work was done in writing, rather than in public speaking, unless we include in this term the teaching of politics and of parliamentary law, with the art of presiding and conducting public meetings. Her most popular book was the Woman's Manual of Parliamentary Law (Boston, 1891), a work that was a recognized standard. For ten years, Shattuck served as president of the National Woman Suffrage Association of Massachusetts. She was also president of the Boston Political Class, which she has conducted for seven years, and in which the science of government and the political topics of the day were considered. She was the founder of "The Old and New" of Malden, Massachusetts, one of the oldest women's clubs in the country. She was a member of the New England Woman's Press Association. On June 11, 1878, she married Sidney Doane Shattuck. She died of pneumonia at Malden Hospital, March 24, 1937. She was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts.

-

PersonHazard, Rebecca Naylor ( 1826 – 1912)Rebecca Naylor Hazard (née Rebecca Ann Naylor) was a 19th-century American philanthropist, suffragist, reformer, and writer from the U.S. state of Ohio. With a few other women, she formed the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri and an Industrial Home for Girls in St. Louis. She organized a society known as the Freedmen's Aid Society, and served as president of the American Woman Suffrage Association. She was born in Woodsfield, Ohio, November 10, 1826, the daughter of Robert F. Naylor (born in Pennsylvania, but lived mostly in Virginia) and Mary Bettis Archbold (of Virginia). Till the age of 14, she studied at Monroe Institute and the Marietta Seminary. The family then moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, and later to Quincy, Illinois. In Quincy, in 1844, while still a teenager, she married William Tweedy Hazard, of Newport, Rhode Island. In 1854, she united with other women in establishing an Industrial Home for Girls in St. Louis. For five years she was on the board of managers of that institution, which has sheltered thousands of homeless children. At the breaking out of the American Civil War, Hazard, who was an ardent Unionist, engaged in hospital work, including the care of sick and wounded soldiers. She helped to organize the Union Aid Society and served as a member of the executive committee in the great Western Sanitary Fair. Finding that large numbers of African American women and children were by the exigencies of war helplessly stranded in the city, Hazard sought means for their relief. They were in a deplorable condition, and, as the supplies contributed to the soldiers could not be used for them, she organized a society known as the Freedmen's Aid Society, for their special benefit. At the close of the war, that society was merged in an orphan asylum. Closely following that work came the establishment of a home for women, which was maintained under great difficulties for some years, before being abandoned. With Mary Foote Henderson, Hazard co-founded the School of Design for women in the field of decorative art. It later became part of the Woman's Exchange. Deeply impressed with the disabilities under which women labor in being deprived of political rights, Hazard, Virginia Minor, Anna Clapp, Lucretia Hall, and Penelope Allen, met in May 1867, and formed the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri. Devoted to this cause, Hazard gave it her attention for many years, filling the various offices of the association, and also serving one term as president of the American Woman Suffrage Association. She authored the popular suffragist song, "Give the Ballot to the Mothers" which was sung by a choir at the first convention of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association in November 1889. In 1870, the city of St. Louis framed into law the Social Evil Ordinance, which legalized and set out to regulate prostitution. Hazard, who disagreed with the statute on a moral level, advocated against it in both public and private scenes. Three years later, she met with other women and organized an appeal to the legislature through a petition campaign to rescind it. The law was repealed by the Missouri Legislature in 1874. The call for the formation of the association for the advancement of women, known as the Woman's Congress, was signed by Hazard, and she continued to be a member of that body, contributing at various times to its sessions the following papers: "Home Studies for Women," "Business Opportunities for Women," and "Crime and its Punishment. After the death of her husband, in 1879, Hazard mostly retired from public work, but at her home in Kirkwood, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis, a class of women met each week for study and mutual improvement. As a result of these studies, Hazard published two papers on the "Divina Commedia." She also wrote a volume on the war period in St. Louis. Her contributions to local and other papers were numerous. Hazard was a member of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and of the American Akademe, a philosophical society having headquarters in Jacksonville, Illinois. She died in Kirkwood in 1912.

-

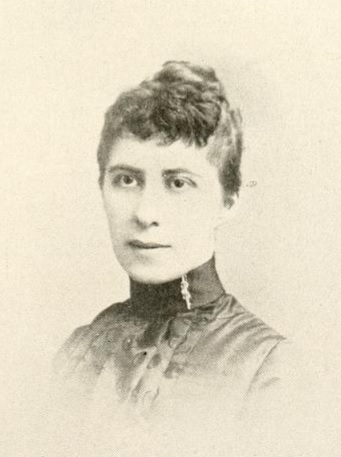

PersonGuiney, Louise Imogen (1861 - 1920)The daughter of Gen. Patrick R. Guiney, an Irish-born American Civil War officer and lawyer, from County Tipperary, and Jeannette Margaret Doyle, she was raised Roman Catholic and educated at the Notre Dame convent school in Boston and at the Academy of the Sacred Heart in Providence, Rhode Island, from which she graduated in 1879. Over the next 20 years, she worked at various jobs, including serving as a postmistress and working in the field of cataloging at the Boston Public Library. She was a member of several literary and social clubs, and according to her friend Ralph Adams Cram was "the most vital and creative personal influence" on their circle of writers and artists in Boston. In 1901, Guiney moved to Oxford, England, to focus on her poetry and essay writing. She donated a crucifix sculpture to the church of St Mary and St Nicholas, Littlemore, to mark the centenary of Cardinal Newman's birth in 1901. She soon began to suffer from illness and was no longer able to write poetry. She was a contributor to The Atlantic Monthly, Scribner's Magazine, McClure's, Blackwood's Magazine, Dublin Review, The Catholic World, and the Catholic Encyclopedia. With Gwenllian Morgan, Guiney prepared materials for an edition and biography of the seventeenth-century Anglo-Welsh Metaphysical poet Henry Vaughan. Neither Guiney nor Morgan lived to complete the project, however, but their research was used by F. E. Hutchinson for his 1947 biography “Henry Vaughan”. Guiney died of a stroke near Gloucestershire, England, at age 59, leaving much of her work unfinished. Her life and works caught the attention of the historian and writer Eva Tenison who unusually published books about her under her own name. In the year after she died Tenison published, Louise Imogen Guiney; an Appreciation. In 1923 she published Louise Imogen Guiney: Her Life and Works, 1861-1920[9] and A Bibliography of Louise Imogen Guiney, 1861-1920. Tenison also published, The Recusant Poets: An Unpublished Work of Louise Imogen Guiney and Fr. Geoffrey Bliss, S.J.

-

PersonRossetti, Maria Francesca (1827 - 1876)Maria Francesca Rossetti was an English author and nun. She was the sister of artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Michael Rossetti, and of Christina Georgina Rossetti, who dedicated her 1862 poem Goblin Market to Maria. She was the author of “The Shadow of Dante: Being an essay towards studying himself, his world, and his pilgrimage” (published 1871). She also acted as a governess during the years of family hardship brought on by her father's failing health, and tutored a young Lucy Madox Brown, a future sister-in-law. At the age of 46, Maria joined the Society of All Saints, an Anglican order for women. Lucy Madox Brown wanted to paint her in her habit. She made an English translation of the Monastic Diurnal for her order, The Day Hours and Other Offices as Used by the Sisters of All Saints, which was used by her order until 1922. She, along with her sister Christina, donated her time to the St. Mary Magdalene Home for Fallen Women in Highgate. She unsuccessfully attempted to convert her agnostic brothers on her deathbed. Maria died of ovarian cancer in 1876, despite drawn-out treatments to try to drain the tumor. She was buried in the convent plot at Brompton Cemetery.

-

PersonGray Cone, Helen (1859 - 1934)Cone was born in New York and attended the Normal College of the City of New York, later renamed Hunter College. She graduated in 1876 as a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and became an instructor in the Normal College English department. In the 1880s she served as president of the Associate Alumnae of the Normal College. Her first book, Oberon and Puck: Verses Grave and Gay was published by Cassell, New York, in 1885. The New York Times received it well, saying, "Miss Cone has the rare talent of compression and the wit not to attempt too high a flight at first." The book was reprinted by Houghton Mifflin in 1893, after that press released her The Ride to the Lady in 1891. She wrote fiction as well in this period, publishing a short story in Harper's Magazine in 1886. In 1899, she was elected to the Professorship in English after the death of her predecessor in the position. Though the Normal College admitted only female students at the time, Cone was the first woman to hold a professorship there. As sole holder of the title, she was considered department head, a title she retained as the department grew. Her Soldiers of the Light was published by Richard G. Badger of Boston in 1910. Stephenson Browne commented in the New York Times: "Miss Cone refrains so steadfastly from the arts of the self-advertiser that only those who read all the magazines know how large is the volume of genuine poetry she annually presents in the best of them." A poem from the book, "The Common Street," was published in the Times the following year; it praises the sunset which bursts suddenly into the New York landscape, turning the common street and its denizens, "Each with his sordid burden trudging by," into "A golden highway into golden heaven, / With the dark shapes of men ascending still." Poetry collections A Chant of Love for England (New York: Dutton, 1915) and The Coat Without a Seam (New York: Dutton, 1919) followed. In addition to poetry and fiction, she wrote literary criticism (her 1890 history of American literature was republished in a 2000 anthology), co-edited Pen-Portraits of Literary Women with Jeanette L. Gilder (New York: Cassell, 1887) and provided notes for Houghton Mifflin's Riverside editions of Shakespeare's Macbeth (1897), Hamlet (1897), Merchant of Venice (1900), and Twelfth Night (1901). A volume of her selected poems was published as Harvest Home (New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1930). She was awarded honorary degrees by New York University in 1908 and Hunter in 1920.

-

PersonKein Wetherill, Julia (1858-1931)Julia Kein Wetherill was born in Woodville, Mississippi and educated in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1884, she moved to New Orleans where two years later she married Marion A. Baker, editor of the newspaper New Orleans Times-Democrat. In 1916, she was recorded as being the Sunday editor of that newspaper. She wrote "Literary Pathways", a book review column, and "Innocent Bystander", a column concerning the theater and music, both of which appeared in the New Orleans newspapers. She published a number of short stories in publications including Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, The Century Magazine, and The Critic, often under the name Julie K. Wetherill. Baker's funeral was held in Christ Church Cathedral, and she was buried in Saint Louis Cemetery.

-

Text

-

PersonBlow, Susan Elizabeth (1843-1916)Susan Blow was the eldest of nine children. She was the daughter of Henry Taylor Blow and Minerva Grimsley Blow. Blow received her education from her parents, various governesses, private tutors, and schools, due to her family's social status. Her parents highly valued education for their daughters, although this was uncommon for Victorian families. Henry Blow contributed funds to build a public school which was named after him. At age eight, Susan was enrolled at the William McCartney School in New Orleans, Louisiana. She attended classes there for the next two years. Blow and her sister Nellie enrolled in the New York school of Henrietta Haynes at age sixteen. They were forced to return home due to the outbreak of the Civil War. Blow tutored her younger brothers and sister, and she taught Sunday school at Carleton Presbyterian Church during this time. Blow never married. She was considered a member of the St. Louis School, a literary, philosophical, and educational movement. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Henry Blow to be the minister to Brazil in 1869, and Susan went with him as his secretary. She quickly learned Portuguese during the next fifteen months. Her bilingual ability helped to ease trade communications between Brazil and the United States. Blow went abroad to Europe in 1870, along with her mother and siblings. Susan began studying the philosophies of Hegel and the American Transcendentalists while in Europe. Susan came across the kindergarten teaching methods of German idealist and philosopher Friedrich Fröbel. Fröbel believed in "learning-through-play" and cognitive development. Susan was inspired to bring these ideas to St. Louis, and her father offered to set up a kindergarten as a private school. Susan felt that she was going to be able to serve the children better through the public school system. In 1871 Blow traveled to New York, where she spent a year being trained at the New York Normal Training Kindergarten, operated by Fröbel devotee Maria Kraus-Boelté. Blow returned to St. Louis in 1873 and opened the nation's first public kindergarten in Des Peres School in Carondelet, which by then had been annexed by the City of St. Louis. Blow was able to open her school, in part, thanks to the support she received from William Torrey Harris, the superintendent of schools in St. Louis. Harris believed the greatest educational concern of the time was the number of young children who dropped out of school. Blow believed a kindergarten system would improve the dropout rate, for children would be starting school at an earlier age. Although he originally resisted the idea of a public program, he was persuaded by the school board's support of Blow, her background, and her proposal to direct the program herself. In 1874 Blow opened a training school to accommodate the in-demand kindergarten teachers. Those in training spent mornings volunteering in the kindergarten classes and afternoons and weekends studying Fröbel's ideas. Through her work, Blow played a significant role in the history and development of early childhood education. She died in March 1916 in New York City. Most references state she died on March 26, but her tombstone at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis declares that she died on March 27.

-

PersonVale Blake, Euphemia (1817-1904)Euphemia Vale was born in Hastings, England, 1817. Her parents were Prof. Gilbert Vale and Hepsibah (Johnstone) Vale. She came with her father, mother and other members of the family to New York City in 1823. Her father was well-known as an author, publisher, inventor, public lecturer and a professor of astronomy and other branches of mathematics, making a specialty of navigation. In New York City, in 1842, she married Dr. Mayo Gerrish Smith, son of Foster Smith. Soon after her marriage, she came with her husband to Newburyport, Massachusetts, and lived for some months in the family of her father-in-law, on Smith's court, removing later to a dwelling house on Essex street, where her husband had an office fitted up for his use as a dental surgeon. After the discovery of gold in California, in 1849, Dr. Smith went to the Pacific coast, and remained there seven years. During his absence, Blake was engaged in literary work. She was a frequent contributor to the Newburyport Herald, taking the editorial duties whenever the chief was absent. She also edited a weekly literary paper the Saturday Evening Union, and supplied leading articles for the Watch Tower. At that time, she was also writing for the North American Review and Christian Examiner, all the editorials for the Bay State, a weekly published in Lynn, with occasional articles in the Boston daily journals, the Transcript, Traveller, Atlas, and others. It was in the Atlas that one of her articles, in 1853, started the movement for revising the laws of Massachusetts and causing the adoption of that law limiting the franchise to those capable of reading the Constitution of the United States. She furnished a series of "Letters from New York" to the Boston Traveller and wrote essays for the Religious Magazine. Then, for the New York Quarterly, she did much book reviewing. She also wrote for the Constellation, edited by Park Benjamin Sr. In 1854, she wrote and published the history of the town of Newburyport, and a scientific work on the use of ether and chloroform applied to practical dentistry. She wrote the first considerable criticisms of Dickens' early novels as they appeared, and also the early works of George William Curtis. In 1857, she removed to New York, and was there granted a decree of divorce from her husband. In 1859 to 1861, she regularly supplied the Crayon, an art magazine published in New York, with elaborate articles on literature and art. In 1863, she married, in New York, Dr. Daniel S. Blake. After her second marriage, she resided in Brooklyn. In 1871, Blake furnished historical articles to the Catholic World on Milesians. Next followed articles for the Christian Union, and, at the request of Henry Ward Beecher, a few short stories. A little later, she contributed essays to Popular Science Monthly. One of her productions was printed in the Brooklyn Eagle of 23 November 1871, discussing the riparian rights of Brooklyn to her own shoreline. It was a historical piece of all the legislation on the subject, from colonial times to the date of publication. The late Chief Justice Joseph Nielson, of the city court, remarked that "the argument was unanswerable." In 1874, she published Arctic Experiences (New York), to give a correct history of the Polaris expedition and Captain George Tyson's ice drift, and containing also a sketch of all the preceding expeditions, both American and foreign. In 1879, and subsequently, Blake wrote regularly for the Oriental Church Magazine. She wrote several lectures on historical and social topics for a literary bureau in New York, which were repeatedly delivered by a man who claimed them as his own. She also wrote a book on marine zoology and a series of articles on "The Marys of History, Art and Song." She occasionally wrote in verse. Euphemia Vale Blake died 21 October 1904 at her home in Brooklyn, and is buried in that city's Green-Wood Cemetery. The E. Vale Blake papers are held by the Brooklyn Historical Society.

-

PersonFuller Ossoli, Sarah Margaret (1810-1850)Sarah Margaret Fuller, sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movement. She was the first American female war correspondent and full-time book reviewer in journalism. Her book Woman in the Nineteenth Century is considered the first major feminist work in the United States. Born Sarah Margaret Fuller in Cambridge, Massachusetts, she was given a substantial early education by her father, Timothy Fuller, a lawyer who died in 1835 due to cholera. She later had more formal schooling and became a teacher before, in 1839, she began overseeing her Conversations series: classes for women meant to compensate for their lack of access to higher education. She became the first editor of the transcendentalist journal The Dial in 1840, which was the year her writing career started to succeed, before joining the staff of the New-York Tribune under Horace Greeley in 1844. By the time she was in her 30s, Fuller had earned a reputation as the best-read person in New England, male or female, and became the first woman allowed to use the library at Harvard College. Her seminal work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, was published in 1845. A year later, she was sent to Europe for the Tribune as its first female correspondent. She soon became involved with the revolutions in Italy and allied herself with Giuseppe Mazzini. She had a relationship with Giovanni Ossoli, with whom she had a child. All three members of the family died in a shipwreck off Fire Island, New York, as they were traveling to the United States in 1850. Fuller's body was never recovered. Fuller was an advocate of women's rights and, in particular, women's education and the right to employment. Fuller, along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, wanted to stay free of what she called the "strong mental odor" of female teachers. She also encouraged many other reforms in society, including prison reform and the emancipation of slaves in the United States. Many other advocates for women's rights and feminism, including Susan B. Anthony, cited Fuller as a source of inspiration. Many of her contemporaries, however, were not supportive, including her former friend Harriet Martineau, who said that Fuller was a talker rather than an activist. Shortly after Fuller's death, her importance faded. The editors who prepared her letters to be published, believing that her fame would be short-lived, censored or altered much of her work before publication.